Bedlam, Globe Theatre

reviewed for The Spectator, 12 September, 2010

Rose Leslie in Bedlam

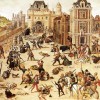

The Southbank has always been an anarchic place. Shakespeare’s Globe proudly reminds visitors that Elizabethan theatres were considered far too lawless – and, implicitly, too much fun – to be licensed within the city limits. After years of rubbing shoulders with gamblers, pimps, and bear-baiters, by 1815 most theatres had advanced to the semi-respectability of the West End, only to be replaced in Southwark by their natural heirs, the lunatics of Bedlam. For fashionable Londoners, the hospital’s patients fulfilled much the same role as Shakespeare’s actors had done before them, providing a voyeuristic thrill on the hospital’s packed weekly open days, a chance to mock or mediate on the wilder extremes of human pathos, before the closing bell sent the spectators home to continue everyday life, leaving the performers safely confined and controlled. Nowadays, we just flick a switch and leave the lunatics on hold in the Big Brother house.

Playwright Nell Leyshon has clearly taken pains to research the complexities of mental illness. Throughout the publicity material, forensic psychiatrist Dr Tim McInery speaks glowingly of the hours she spent working with his patients at the Royal Bethlem Hospital, the modern incarnation of Bedlam, which is now at the forefront of attempts to humanely rehabilitate psychiatric patients. So it’s a real shame that Bedlam fundamentally fails to break away from standard literary stereotypes of the lunatic.

From the off, the asylum is a riot of debauched sexual predators, religious maniacs and murderous schizophrenics. By the end, the reform-minded new governor is laudably urging us to understand that cases of mental illnesses are as individual as those of physical illnesses, that they are just as likely to be curable, and constitute just as little reason to segregate society into the healthy and the dangerous. It’s a message we need to hear: this month, a study led by the University of Oxford caused surprise when it ruled that suffers of bipolar disorders are no more likely to be violent than other members of the public, unless their condition is exacerbated with substance abuse. Public fear of the mentally ill is still entrenched: 36% of people think that having a mental illness means being prone to violence, and a frightening 59% of people would include “has to be kept in a psychiatric hospital” in their definition of mental illness – which in practice, given that 1 in 4 people will suffer from mental distress at some point, would look like an apocalyptic landscape of Britain bankrupted by Bedlams. But though the governor tells us to try for greater nuance, it’s hard to find it in the portrayals of his patients. There’s a clear division between the sympathetic cases – the sane woman cruelly imprisoned after an illegitimate birth, the pure country maiden distracted by her sweetheart’s departure – and the violent zanies drawn with all the subtlety of an Georgian version of Eastenders. The latter, disturbingly, are played for cheap laughs. Are we supposed to roar with laughter as the alcoholic gropes every female inmate in sight, and even – ooh Matron! – the nurse? Leyshon is keen to implicate the audience in the voyeurism of the asylum’s visitors – we are, as we are repeatedly reminded, gawping, just like them. But when the least sympathetic characters are subjects for slapstick, it’s little wonder that the groundlings at Press Night guffawed away as at a riotous comedy. Had Leyshon even once tricked us into mocking a character of genuine sympathy, we might have felt more remorse.

Nonetheless, the play is full of strong performances. Finty Williams is superb as a witty young widow, and Rose Leslie invests Leyshon’s regurgitation of Ophelia with the same ethereal dignity as when she impressed in last year’s BBC drama, New Town. Leslie seems effortlessly captivating, her other-worldliness well matched by James Lailey’s puckish Tom-O-Bedlam. Jason Baughan brings real pathos to the climactic scene in which Bedlam’s own doctor is diagnosed with mania, a surprising moment of poignancy given the simplicity with which Leyshon draws the stereotype of this corrupt, drunken cynic in the first half of the play.

Such inconsistencies lie at the heart of the text. The influence of Hogarth’s Gin Lane permeates Leyshon’s London – Ella Smith’s bawdy gin doxy regales us with tales of alcoholic London, sitting on the steps of the Globe’s yard in an exact recreation of the famous pose, although thankfully she only lets her gin bottle slip instead of a baby. But the chaos of Hogarth’s scenes is reflected in the play’s structure as much as its subject – we move as through a boozy haze of scenes, subplots and dramatic styles. The first half feels like Lionel Bart’s take on Punch-and-Judy, while the second earnestly tries to play catch-up with the “serious issues”, but hasn’t inherited enough character development to make much impact. Without a unified structure, a play with great potential fails to engage. Uncomfortable, but also unchallenging.