Spectator Debate Report: Secularism is a Greater Threat to Christianity Than Islam

The Spectator hosted a debate at the Royal Geographic Society yesterday evening with a rather meaty motion: “Secularism is a greater threat to Christianity than Islam”.

Published at The Spectator, 30 June, 2011

Last night’s Spectator debate on the motion “Secularism is a greater threat to Christianity than Islam” was marked by a highly personal level of investment from the speakers, a sudden swing in the vote, and the uncharacteristic sight of Chair Rod Liddle acting as the most conciliatory person in the room. Although the debate ranged far and wide, at its heart was an old-fashioned contest between traditionalists interested in the cultural hinterland in which society changes, and rationalists who use the calculus of terrorism statistics and murder rates. Liddle introduced Damian Thompson as “further to the Right than a fishknife”. But when Thompson’s opponent for the night, Douglas Murray, was introduced as the only possible speaker who might outflank him on the Right, it was a reminder of just how many attitudes can fall under the label of “right wing” nowadays.

The Reverend Timothy Radcliffe OP opened for the motion. To Radcliffe, Christianity is not threatened by attempts to separate Church and State. The current and previous governments, he added wryly, both made regular announcements about the importance of faith involvement in community. Rather, Christianity is threatened by fundamentalist secularism, which argues that the only valid truths that are scientific. Christianity, Radcliffe claimed, has never excluded science. Indeed, St Albert the Great insisted on testing every hypothesis concerning nature that he encountered, even carrying around an iron bar with him to test on every passing ostrich the claim that an ostrich could ingest iron. By contrast, “secularism, by definition, makes totalitarian claims – only a Communist dictator could come up with a phrase that his writers could “engineer the soul”.

Dr Patrick Sookhdeo, a convert from Islam and senior Anglican evangelist, opposed. He drew on his own experience of persecution in Pakistan, and his understanding of Islamic history. “Never and nowhere has secularism destroyed Christianity, but the same cannot be said for Islam”. Moving with familiarity through a rapid range of examples, he paid particular attention to the Muslim conquest of Syria in 635–8. Notorious for its prescription of the death penalty for apostates, “Islam is unique among world religions on the pressure it exerts on other faiths.” Unlike Christianity, Islam legislates for all areas of public and “secular” life, Sookhdeo noted. And even in the 21st century, we have seen Islamic aggression: in Smyrna, Assyria, the Armenian genocide, the Sudanese civil war and the decimation of the Christian population in Iraq. Only in an Islamic state could Asia Bibi find herself on Death Row, two of her most prominent political defenders murdered.

Damian Thompson began his response by praising Sookhdeo’s support for persecuted Christians. He was clear in his condemnation of Christians who fail to confront Islam, or to defend their faith. But he argued that Christian timidity can be directly attributed to the fact that Western Christianity itself has become secularised. The Church of England, even the Catholic Church, has become infected by relativism, while Christians who defend “unfashionable” or socially conservative viewpoints find their cultural reference points eroded by social scorn and religious illiteracy.

The Spectator blogger and Observer columnist Nick Cohen gave a secular defence of the Enlightenment. He also attempted to draw together the disparate strands of the debate that had at times focused on Western religion, at times on Developing World religion. “Christianity in the West has been made temperate by the Enlightenment”, but the same is true neither of Islam, nor of Christianity in the wider world. Rejecting Father Radcliffe’s definition of “fundamentalist secularism”, Cohen argued that secularism chiefly seeks to establish a framework for pluralism. “It is the only way for multiculturalism — and therefore the only way that people born into religious communities can have access to new ideas”.

For Tariq Ramadan, Cohen’s insistence on scepticism typified the arrogance of secularists “who are dogmatic about the superiority of doubt”. Ramadan insisted upon the diversity of interpretations of Islam, arguing that reductionist descriptions of Islam by its opponents only increase tension and conflict. Many of the most oppressive tactics by Muslim dictatorships, he noted, have been supported by Western, secular patron-states. But at the highest levels, Christian leaders recognise that Muslims share their concerns about the soullessness of modern society, and the need to put the challenge of difficult ethical questions at the heart of our spiritual lives.

Douglas Murray retorted that he’d recently been asked if, seeing Ramadan so often at the same debates, there was a danger they might become friends. “No way!” Murray passionately condemned the claim that the social pressures exerted on Christians by Western secularists can be compared to persecution in the Islamic world, reeling off a sobering list of incidents of Islamic violence monitored in the last fortnight alone. Even in Britain, Muslims risk death for opting out of the communities into which they are born — secularists may be aggressive, but they have never blown up British buildings. Murray even reminded the audience of Pope Benedict’s Regensburg address: “it was a lecture that mainly attacked secularism, but not one secularist made a violent threat in response. There was one throw-away line about Islam, and within days, a nun had been killed in reprisal in Somalia”.

The debate, already heated, did become particularly fierce at this point. Douglas Murray’s attack on “Western Christians who ignore the plight of Catholics in Pakistan but complain about nasty anti-Catholic jibes at the dinner table”, earned a complaint from Thompson: “nothing in my life has ever been so misrepresented”. Thompson was still expressing his disappointment on Twitter several hours later.

But underlying the spat was a genuine and intriguing difference of approach. For all the speakers in the affirmative, secularism was perceived as a threat because it eroded the vocabulary of faith, disconnecting contemporary culture from the aesthetics of Christian meaning. So is killing a culture as absolute as killing a human being? Not for Murray and Cohen, but perhaps for some of the audience.

And that audience, including many regular CoffeeHousers, was on top form. Questions ranged from the nature of evil to the practicalities of evangelism. Meanwhile, Dr Sookhdeo took Professor Ramadan to task on his description of a liberal “amorphous” Islam, challenging him to name a secular or Christian country that executed converts. And just when it seemed that the debate would stretch to whole new horizons (“China!” interjected Father Radcliffe, “we haven’t talked about China!”), it was time for the results of the vote.

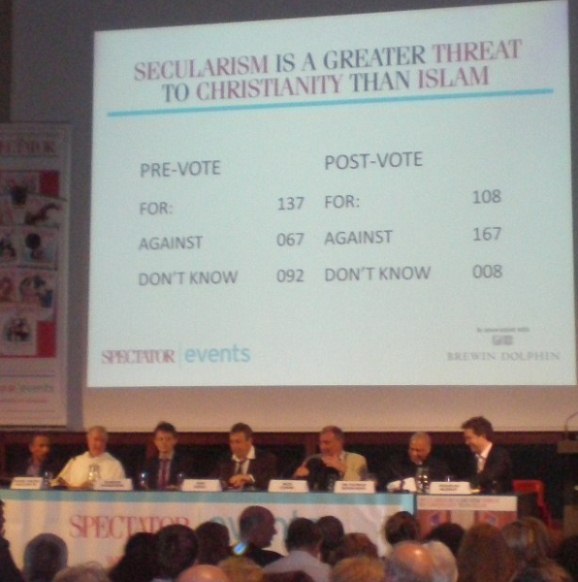

Before the debate:

For: 137

Against: 67

Abstain: 92

After the debate:

For: 108

Against: 167

Abstain: 8