Ground Zero

On artistic responses to September 11.

Published in two parts at The Spectator: on 10 October 2011 and 11 October 2011

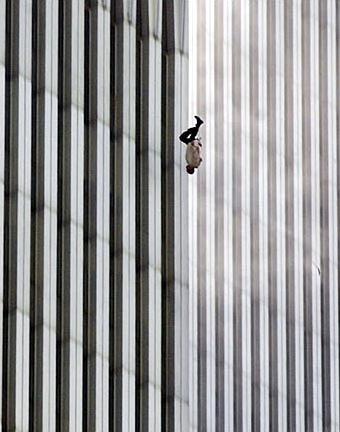

The Falling Man, by Richard Drew, September 11, 2001

There’s a moment in Rupert Goold’s latest production, Decade, in which a gaunt widow (Charlotte Randle) stares up and into the empty space just left of where the North Tower used to stand at Ground Zero, New York. Each day, she tells her listeners, she is staring not at the space where the tower used to be, but trying to find the patch of air through which her husband might have tumbled, voluntary but unwilling, to his death.

She doesn’t have to describe exactly what she sees in her mind’s eye, because we’ve all seen it ourselves. It’s a simple, iconic image. A photograph taken by Richard Drew, a photograph we all know, even if we’ll never know the name of its subject. A photograph called The Falling Man.

If there’s a great piece of art to come out of the 9/11 attacks, it won’t be Decade, but it might be The Falling Man. If it succeeds where Decade fails, it’s because it’s simple, but intimate, recording an external reality, but rooted in the internal response of the viewer.

The sight of a man in freefall, toppling between two alternate modes of death, outlasts the sheer news value of the image because it forces us to place ourselves in the burning window on the 107th floor of a building – any building – and wonder. Would we, could we, jump? Even people like I, who morally oppose suicide and euthanasia, are scared most by finding that somewhere within us the answer might be ‘yes’.

And it’s because of these moral issues, issues of courage and shame, that New Yorkers have been uncertain how to collectively react to the workers who jumped from the Twin Towers – and reluctant to identify the subject of The Falling Man. It could have been Jonathan Briley, the asthmatic afraid of death by smog, or, less likely, Norberto Hernandez, whose Catholic family insisted that researchers ‘clear his name’ of the shame of suicide.

Suicide is a tuneless word for the choice that 200 made that day – if it was a choice. Most may have been simply blown out of the building by the force of the heat, or stumbled blindly in the smoke. Understandably, therefore, the New York medical examiner’s office does not classify such deaths as ‘suicides’ or ‘jumpers’, but includes them on the list of victims killed inside the building.

As a spokesman bruskly put it, ‘a “jumper” is somebody who goes to the office in the morning knowing that they will commit suicide’ – although there are plenty of survivors who feel this decision, too, brushes the reality of their relatives’ deaths under the carpet, institutionalizing the view that jumping in such circumstances was something shameful. Richard Pecarello, who suspects his fiancée jumped to her death, is comforted by the idea that she “chose death on her own terms“. In a nation determined to view its response to 9/11 as a victory, the urge to imaginatively gift its dead some control over their final moments is as powerful as the need to insist that they all died courageously.

But the subject of The Falling Man was a victim, was murdered. And one of the darkest aspects of viewing the photograph is that is forces us to imagine another pair of eyes sharing the image with us, a pair of eyes triumphing in this fearful descent. The eyes of the plotter, somewhere in an unknown land.

It’s a dangerous game that much 9/11 art has played, the challenge of fixing the private, emotional experience of grief, while also tracing its connection with motivations of terrorists and politicians. There’s as much scope here for cheap mob manipulation in poor art as there is in political speechwriting: the artistic response to bereavement and burning flesh is visceral, the literature of global politics should be meditative.

Decade tries and fails to bridge this gulf. A hodge-podge of sketches by 19 different writers, it promises in the programme literature to offer an exhaustive account of the ‘two towers, ten years, thousands of opinions’ at stake. For starters, this is simply overambitious. But the shortcuts that Goold is therefore forced to take in weaving these strands together are manipulative

and deceitful.

There’s plenty of emotional pornography – women weeping for their husbands, childless parents, a survivor obsessively scratching her eczema as if to repulse any potential suitor – but once Goold has the audience warmed up and weeping, we’re bombarded with the politics.

In the glass windows through which we’ve seen hordes of World Trade Centre workers clutch at each other and panic, we suddenly see a terrified Middle Eastern woman, clutching at her child as she shelters him from an approaching American soldier, unsure whether or not to fire his gun. It was at this point that I and my companion, a liberal, ultra-urbane American, nearly walked out.

This isn’t to say that art shouldn’t play a role in explaining and forgiving the human beings behind terror. Indeed, it’s one of its crucial functions. The recent instillation by The Wooster Collective hints at this to chilling effect: if these men shared ordinary, interior spaces with us, what might we guess of their own interiority? But Decade chucks in these themes amongst so many other competing problems that it’s forced to do so crudely, clumsily.

There’s a moment when a stand-in for Osama Bin Laden denounces the West for ‘toppling our towers in Lebanon, in Palestine’, for which the demolition of American towers is an equal and opposite action. The light fades on him and rises again on the anguished face of 9/11 widow, struggling to raise teenage daughters on her own. It’s an obvious ploy for emotional impact, but the two narratives are speaking past each other.

Sure, it makes us sigh over cycles of violence and destruction, but it doesn’t tell us anything about the smaller, human steps between a man seeing his homeland burn and becoming a terrorist, or the colder geo-political calculations made by his commanders. The problem of Palestine has certainly inspired plenty of grass-roots antipathy towards the United States, but the callous objectives of Bin Laden himself have always been more firmly rooted in the politics of Saudi Arabia. You wouldn’t learn that here.

Pages: 1 2