The Duchess of Malfi, Sam Wannamaker Theatre at the Globe

reviewed for Conservative Home, 30 January 2014

The last time I saw Gemma Arteton play dead she was lying on James Bond’s hotel bed, her nude body glistening with black oil. I’ve just watched her asphyxiated again, as the doomed title role in John Webster’s Duchess of Malfi, so although this time her skin glitters not with oil but powdered pearls, lit by beeswax candles, I’m tempted to wonder if she’s making a habit of snuff-shows.

Webster is a famously voyeuristic playwright – he’s best remembered by modern movie-goers as a nasty little boy who slowly feeds mice to cats in Shakespeare In Love – so perhaps Malfi isn’t a far cry from Arteton’s back-catalogue of exploitation films. But he’s also a playwright deeply versed in the dynamics of power and the gradations of betrayal. The Duchess marries a commoner for love, and she is sadistically tortured for it, but it’s the murderous courtier Bosola’s slow discovery of his conscience, after years of nihilism, that forms the driving force of this drama. Malfi’s court is built on a vacuum of trust, as well as conscience – aside from the Duchess’ transcendent love for Antonio, all alliances in the play are temporary.

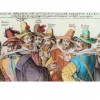

So it’s the incestuous atmosphere of the Globe’s new Wannamaker Theatre, rather than Arteton’s sex-appeal, that should be this production’s big draw. We’re used to thinking of Shakespeare and his contemporaries as men who wrote for the open air (A Midsummer’s Nights’ Dream is al fresco in every possible sense), but in winter, they decamped to claustrophobic indoor spaces. And it’s in such theatres that the darkest Jacobean tragedies were first performed. Four years of academic research and technical craft have gone into the Globe’s replica. Beneath the heavy wooden beams, it’s easy to imagine that the actors are on trial. Formal as a palace, cramped as a prison-cell, it’s a perfect window into the poisonous world of the Duchess of Malfi – a cautionary tale of Italian corruption. Sure, the seats are stiff and painful, wooden benches rather than cushioned stalls, but revenge tragedy was never meant to be a cosy ride.

Occasionally, I have nightmares that I’m back at the Globe’s competitor, the “authentic” Blackfriars Theatre in Staunton, Virginia. Row after row of smiling Americans, each with perfect teeth, welcome me to “a Renaissance reenactment” until I wake, sweaty and screaming. I’ve never believed that we can recreate the Jacobean theatrical experience. The recent all-male productions of Richard III and Twelfth Night tried to perform exactly as Shakespeare’s company did – as a result, I choked on my giggles when the first ghost appeared to haunt Mark Rylance’s Richard, wearing no more sophisticated costume than a starchy white sheet. Theatre relies on the audience’s imagination to convince: we no longer possess an early modern imagination, so our response to early modern visual cues is inevitably different. A bed sheet might have been an avant-garde costume for a ghost in 1591 (rusty armour was more conventional) but nowadays it’s impossible to watch without thinking of Scooby-Doo or cheap Halloween costumes. Testing out original practices is a useful research exercise – it’s fascinating to discover, for example, that a crucial scene in Malfi really could take place entirely in the dark – but it rarely makes for great theatre.

So I’m hoping the Globe’s director, Dominic Dromgoole, has inaugurated the Wannamaker as he means to go on: with a perfect marriage of old and new. He’s not limited by the formality of indoor Jacobean conventions – actors spring from unexpected corners, madmen harass the front row audience and an exit through the audience is used to far fuller effect than in the boxed-in productions at Staunton. Yet authentic elements are used to full effect: Bosola wonders if any man can escape the stars, only to look up and see the painted constellations of the theatre’s ceiling above him, fixed and immovable. The Duchess’ brother, Duke Ferdinand, hints at his incestuous desires while complaining of ‘the imperfect light of human reason’, and the candles flicker appropriately. And as is traditional, the performance ends with a jig. But this dance is no Renaissance Fairre jollity. Instead it is cold, ghostly and static, the glazed face of each participant lifeless as a marionette.

And it’s those faltering figures, weaving like clockwork in and out of each other, that will haunt me from this production. It’s a snapshot of a true ensemble piece: James Garnon is a crisply urbane Cardinal, in control of everything but the hour of his death; Alex Waldmann an endearingly vulnerable Antonio; David Dawson a credibly reckless Ferdinand, if more fey than Harry Lloyd’s thuggish version two years ago. Arteton herself is refreshingly innocent, but dainty rather than dynamic. But fortunately, the ensemble is simply too engaging for us to notice any absence of star power. It’s a wonderful opening for an intriguing new performance space. And you might also get a few cheap thrills.