David Aaronovitch doesn’t have to be female to spot that The Vagenda is frippery

written for The Telegraph, 28 April 2014

“Still, in our society, women are subjected to abuse as bitches and ‘hos’, ridiculed for their appearance and somehow incapable of being bishops. Feminism has gone too far? It’s gone nowhere near far enough. Feminism has gone mad? It ought to be as mad as hell.”

“Still, in our society, women are subjected to abuse as bitches and ‘hos’, ridiculed for their appearance and somehow incapable of being bishops. Feminism has gone too far? It’s gone nowhere near far enough. Feminism has gone mad? It ought to be as mad as hell.”

Those are the words of David Aaronovitch, Twitter-feminism’s latest public enemy. Aaronovitch’s crime? Daring to review a book about feminism, while male. And not being entirely convinced the scanty research that went to it deserved a £100,000 advance. Again, while male.

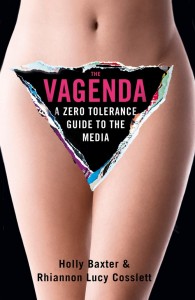

Aaronovitch’s review of The Vagenda: A Zero Tolerance Guide to the Media caused a toxic eruption in the Twittersphere this weekend. No matter that Aaronovitch is as card-carrying a feminist as men come (see above), no matter that his review identifies a key weakness in The Vagenda, that authors Holly Baxter and Rhiannon Lucy Cosslett, editors of the wildly successful blog of the same name, focus disproportionately on the damage glossy magazines do to women, and much less on the reasons why women nonetheless continue buy them. No matter that a number of other, female, well-regarded feminist reviewers have criticized the book in the same terms. For high-profile feminists like Glosswitch, by virtue of being a man who wonders why women buy Cosmo, Aaronovitch must be a defender of “pornography, sex work and page three”, who blames women and women alone for not reporting rapes and for perpetuating FGM.

Attacking people’s right to write, speak or critique on the basis of their gender has never been good for feminism. It’s a short step from “men, know your place”, to “women, know your place”, and a world where women are commissioned to write 80 per cent of op-eds on gender, and men over 80 per cent of op-eds on economics and politics. (Oh hi, trolls! It’s not because women aren’t interested in politics. Trust me.)

I’ve no wish to perpetuate the hoary old lie that feminist debate is particularly bitter – all lively political movements are marked by internal debate. Have you met the Conservative Party? I have always found Glosswitch an eloquent, inspiring writer on feminism, and I think The Vagenda’s original blog is one of the best things to have happened to British feminism in decades. But on this, she’s wrong: there’s no point in tolerating male allies like Aaronovitch only so long as they don’t ask any real questions. Or, if you didn’t already know the man was a committed feminist and you couldn’t Google, making a whole set of assumptions based on little more than the fact of his gender. It perpetuates the one fiction that feminism seeks to dismantle: that gender is destiny.

So, what of the book? In wishing there were more about why these magazines sell, Aaronovitch asks the authors of The Vagenda to look a little deeper at “the most important question, because it takes you to the heart of how women’s chronic insecurity is transmitted.” (Clearly, the words of a heartless man who DOES NOT CARE about women’s insecurity). The authors of The Vagenda make the limp point that “there is still little alternative available in the women’s market”, though they also hit on the start of a much more substantial point, hardly developed: “where else were you supposed to glean information about what other women were doing or thinking?” Before Mumsnet, before Sex and the City, before tampax adverts on TV, the pages of Cosmo were sole arbitrators of communal female experience. They established their power because in the Seventies they were the only place where you could find out where losing your virginity “was really like”; they consolidated it by setting the beauty norms in this new female space.

But as Victoria Sadler points out, this description of magazines went out of date with the internet. The Vagenda’s parent blog is itself a fantastic new space for women to talk honestly, directly, about modern female experience; Everyday Sexism allows us to come together to confront the ubiquity of street harassment. Yet with all these real communities now available, we still reach for the glossy mag, knowing, as we all now do, just how Photoshopped, airbrushed, synthetic it is.

There are answers to this – it’s just that The Vagenda doesn’t raise them. Glosswitch’s own blog actually gives a better answer than The Vagenda ever can: “I’d flick through the fashion and beauty pages and feel vaguely hopeful that I might yet attain full, beautiful womanhood, providing I lost some more weight and bought yet more stuff.” But she’s defending a book that isn’t nearly as sophisticated as she is – not least because it fails to differentiate between different types of women’s magazine. The question of why some women buy Vogue and some women buy Closer (answer: a lot to do with class) is surely important.

Glosswitch argues that as The Vagenda is “primarily aimed at young women”, Aaronovitch has no place reviewing it. Which is the type of logic that says I shouldn’t be allowed to publicly comment on Page 3. But as a young woman, here’s my verdict. The talented young writers who sparkle in 500-word blog posts haven’t yet learnt how to structure a book over 300 pages, and their attitude to evidence is surprisingly amateur: we’re showered with statistics, but there’s not a footnote or source in sight for any of them. From feminism’s bright young stars, this book is a disappointment. And shooting the critics isn’t going to change that.