Feminists should celebrate the closure of Nuts: it was never pornographic enough

written for The Telegraph, 3rd May, 2014

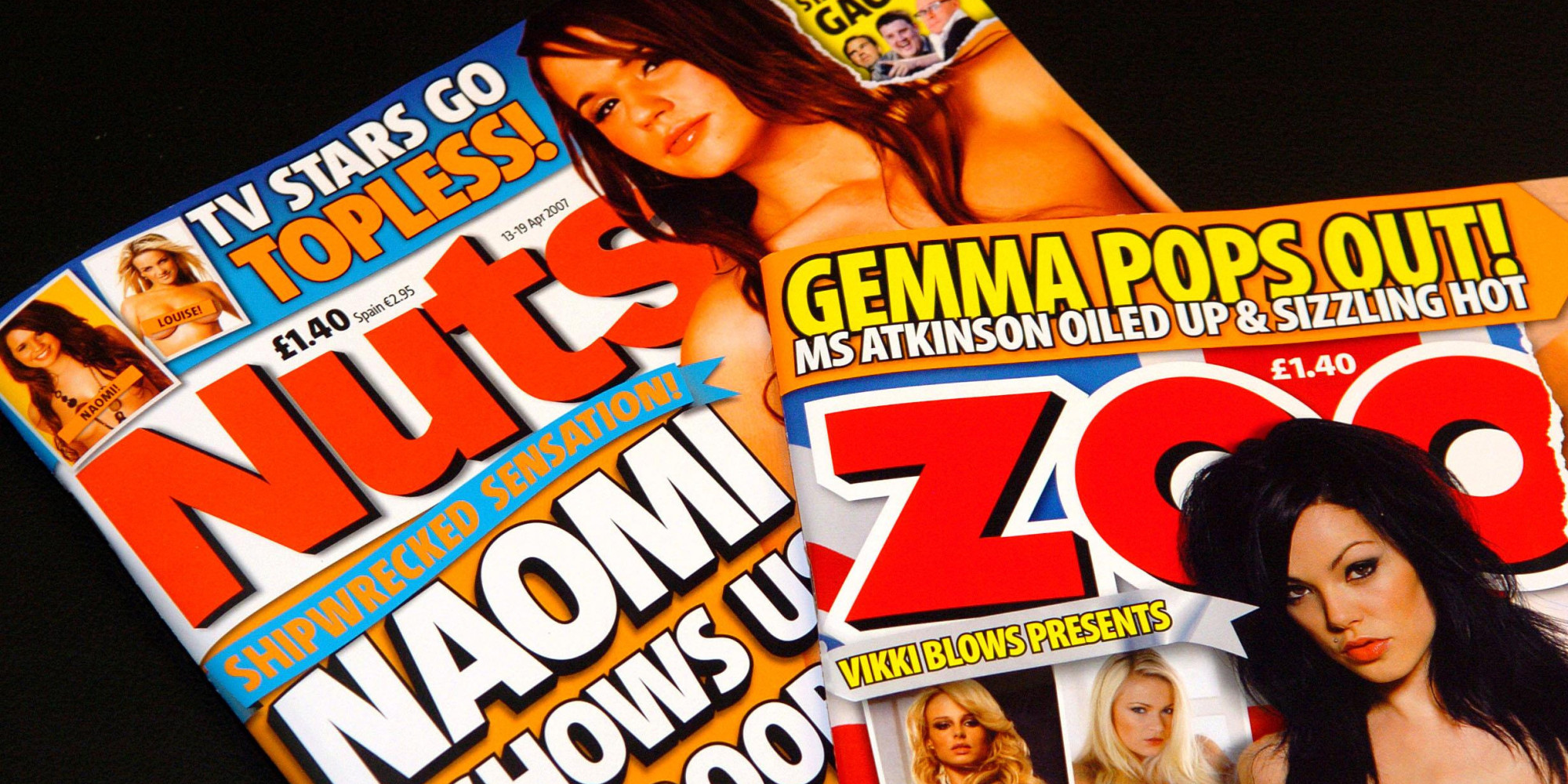

Porn, like the poor, will always be with us. Nuts magazine, which brought polythene packaged nudity down from the top shelf to the middle market, has just unveiled its last ever cover image (a weeping Lucy Pinder, because the real victims of Nuts’ closure are women. Obviously). The standard diagnosis is that Nuts’ readers have migrated to harder, cheaper porn online – consequently, feminist celebrations have been muted. “What’s great about people surfing for porn online instead of paying for it in print?”, intoned one of my more puritanical friends yesterday. But the closure of Nuts should be a cause for a big a party as the feminist movement has ever thrown – because the wretched rag never constituted decent pornography in the first place.

Mankind has always fantasised, and practical wankers have always needed an aide memoire – or in the case of teenage boys, an aide d’espoire. But for most of human history, sexual fantasy has been a private experience – dare we say it, even a shameful one. And the overwhelming majority of men (and women) who use pornography have always been able to distinguish between fantasy life and ordinary life – men who furtively log onto Schoolroom Spankings 1000, obsessively deleting their internet history, don’t tend to spend Parents Evening in a paroxysm of sexual distraction every time their son’s English teacher tries to talk about supporting little Jimmie’s dyslexia.

By contrast, Nuts, Zoo and FHM were toxic. Following Page 3’s lead, they shaped a world in which chatting about a colleague’s breasts became as natural as swapping football tips or iphone apps: objectification as lifestyle choice. FHM is famous for its ‘High Street Honeys’ campaign in which “women from your local High Street” nominate themselves – or more often, are nominated by proud boyfriends – as masturbatory fodder. It’s a direct invitation to the reader to reduce every woman he passes in the street to a piece of meat. A younger friend recently heard that her holiday snaps had been nominated to a lads mag competition by a group of male classmates immediately after she beat them all in University Finals. Lads mags aren’t porn: they’re a tool to keep women in their place.

If that doesn’t seem demeaning, consider the case of “Epic Boobs Girl”, who found that photographs of herself aged fifteen, wearing a strappy top, had been lifted from a social media network and reprinted in Loaded without her consent. More disturbingly, the mag published it under the headline “Find Epic Boobs Girl!”, offering a bounty of £500 to any male reader who identified the girl, and either produced more photographs or “persuaded” her to take part in a Loaded photoshoot. A lengthy campaign of sexual aggression by hopeful Loaded readers followed. When she and her family launched a complaint, the Press Complaints Commission decided it couldn’t take action against the magazine, on the grounds that encouraging readers to stalk an unwilling teenager isn’t an invasion of privacy.

I’ve never felt threatened by a bloke scuttling out of a Soho sex shop with a brown paper bag under his arm. But as Laura Bates attests, every woman has endured a late night train ride as a group of blokes in the carriage pass round a dog-eared copy of Nuts or Page 3 and loudly consider how she might compare with her clothes off. Because unlike real erotica, Nuts has never been about private pleasure: its posters adorn school locker rooms up and down the country so that young men can prove to each other just how heterosexual they really are. Of course, young men have been doing this for generations – one of the perks of studying Elizabethan literature is that I get to read poems like Thomas Nashe’s Merrie Ballad of Nashe, His Dildo (By Holy dame (quoth she), and wilt not stand? / Now let me roll and rub it in my hand!) which Nashe seems to have circulated in manuscript purely so that he could prove to his mates he knew his way around a brothel. But no one could buy a poem like Nashe’s Dildo over a counter at a Tudor Tescos. And unlike Nuts editors, Thomas Nashe couldn’t have stood on a street corner and approached random women to strip for a “Street Strip Challenge”. Remember when Gail West, the precocious classics academic, aced University Challenge? Nuts responded by inviting her for a “tasteful photoshoot”. The message to Britain’s brainy women was clear. You might have three degrees, but here at Nuts we remind you what really matters in a woman – your tits.

This isn’t to say that online pornography is an oasis of healthy sexual exploration. The films of Beeban Kidron, for example, should get us worrying about the number of boys who now watch porn as a bonding activity, and expect their partners to look and act like porn stars. But porn will always be around, below the radar. Humiliating women should be a private sexual fantasy, not a lifestyle choice you can buy in Tesco.

So the closure of Nuts isn’t a victory for Puritans. Nor is it an excuse for a moral panic about the market effects of freely available online porn. It’s a success for anyone who thinks our sexual fantasies should be private. Or who just doesn’t want to see a row of women’s breasts on display the moment she walks into a newsagent.