Power slips from Gloriana’s jewelled fingers

Written for The Spectator, 21st May 2016

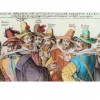

Not-so-Gloriana: Queen Elizabeth I in her early sixties. (Studio of Marcus Gheerarts the Younger, c. 1596)

If you’ve been watching Game of Thrones recently, you’ll have seen an old folkloric fantasy in which a bewitching young prophetess, a charismatic war leader, slips alone into her private chambers and removes an enchanted necklace. Beneath it, she’s just one more withered crone. We, the viewers, having happily feasted on her naked body, now congratulate ourselves on seeing it for what it is: another whore’s trick.

This moralistic antipathy towards the over-preserved female body haunts popular studies of the last years of Queen Eliza-beth I. Nearly a century ago, Lytton Strachey kick-started the grotesquerie genre with Elizabeth and Essex: ‘As her charms grew less, her insistence on their presence grew stronger.’ Elizabeth emerges from Strachey’s text as Norma Desmond with a sceptre, clutching at that cosmetic mask of youth just as it becomes a paler mask of death.

So John Guy, as eminent a Tudor historian as they come, has set himself the explicit task of correcting Strachey’s colourful narrative of Elizabeth’s old age. The result is 400 pages of outstandingly documented scholarly detail. Beneath the rows of footnotes, however, there’s just a hint of Strachey’s distaste for ‘vanity and temper’, or hyper-feminine mood swings, in this portrait of a woman feeling power slipping from her over-jewelled fingers. What emerges more clearly throughout this consistent and well-structured narrative is a deep sense of national decline. As not-so-Gloriana’s body faded, so too did her not-so-happy kingdom.

This has long been Guy’s schtick, and he does it well. In 1995, in an important collection of essays on the last decade, he coined the term ‘the second reign’ to emphasise the radical difference in mood between Elizabeth’s earlier and later years as queen. Back then, he traced this ‘sense of fin de siècle’ to the ‘seemingly dramatic reversal of the queen’s non-interventionist foreign policy’ occasioned by the dispatch of an English expeditionary force to the Netherlands in 1585.

Now, Guy finds his turning point a year earlier, with the assassination of William of Orange in 1584, which just goes to show that all this history-by-critical-dates isn’t what it’s cracked it up to be. But what has marked Guy’s argument consistently over 20 years is a conviction that Elizabeth wrecked her legacy by intervening in a chronically boggy proxy war abroad. A prevaricating diplomat, she was temperamentally unsuited to confrontation and fatally hamstrung by being unable to command her own troops in battle. It is a convincing argument, yet a thoroughly predictable historiography of our time.

It’s surprising, then, that Guy’s heft as a historian really shines through in his description of Elizabeth’s domestic court. He’s sharp on the physical realities of her day-to-day routine: as a female ruler, she couldn’t chat casually to privy counsellors in her bedroom, which left her dependent on contact with the few who had regular access to her, chiefly William Cecil. Guy’s great achievement, which he justly trumpets in his introduction, is to jettison academically ubiquitous Victorian edits of the Calendars of State Papers in favour of his own painstaking trawl through 250,000 pages of handwritten manuscripts from the state papers and copious parchment rolls constituting Elizabeth’s understudied Chamber accounts. The reward is a volume of career-defining scholarly acumen.

Guy applies proper scrutiny, too, to Elizabeth’s careful use of speeches and letters to shape her public image. ‘No ruler has ever better understood the relationship of words to power,’ he writes, and he’s right. We’re offered scrumptious close readings of the courtly messages displayed in pageantry, although some will dispute Guy’s certainty that Lionel Sharpe, the Earl of Leicester’s chaplain, is the ‘most authentic’ source for the famous Tilbury speech. Sometimes, they seem selective: Elizabeth’s speech to Oxford in 1592 hardly gets a look in, perhaps because it articulates too clearly the principle of popular consent that Guy elsewhere insists Elizabeth failed to understand. (If there’s a macro-message to this book, it’s that Elizabeth, long before Charles I, laid the seeds for popular revolt against royal authoritarianism.) And for all his early dismissal of Elizabeth’s posthumous hagiographer, William Camden, he still swallows Camden’s line that Henry IV of France’s conversion to Catholicism drove Elizabeth to translate Boethius’s Consolation of Philosophy, instead of looking for intellectual motivations closer to home.

These are, of course, the quibbles of a fellow Elizabeth obsessive (the Boethius translation is the subject of my current research, hence the predictable snipe). The last time I shared a television screen with Guy, he was rhapsodising over Mary Queen of Scots as an attractive damsel in distress, and I was condemning her as a counter-feminist slut. I still think he’s too soft on Mary, but in print he makes his case with a scholarship that should earn the respect of popular and expert reader alike. With changing fashion, future generations may take issue with Guy’s ghostly vision of Elizabeth’s skull beneath the skin. But flicking through his footnotes, the challenge looks daunting.