Sick Note

written for Standpoint Magazine, June 2009

A massive recent shift in the public agenda of the campaign group Dignitas went largely unnoticed by the media — and therefore unchallenged. Visiting London in April, Ludwig Minelli, the founder of the Dignitas suicide clinic in Switzerland, announced that it was now ready to extend its services to the mentally ill. Without a trace of conscious humour, Minelli added that his scheme would be a boon to the cash-strapped NHS. “For 50 suicide attempts, you have one suicide and the others are failing with heavy costs to the National Health Service. Very costly.”

The story may have slipped under the radar, but it still successfully shifted the parameters of what you can say in public. Crucial for those who care about mental illness, however, was Minelli’s coda. Like most proponents of assisted suicide for the terminally ill, he argues that “suicide is a very good possibility to escape a situation which you can’t alter.”

It is the idea that “depression” and “mental illness” are largely “a situation which you can’t alter” which most damages efforts to increase public understanding of them, and which fuels the stigma attached to sufferers, pariahs beyond hope of a normal existence.

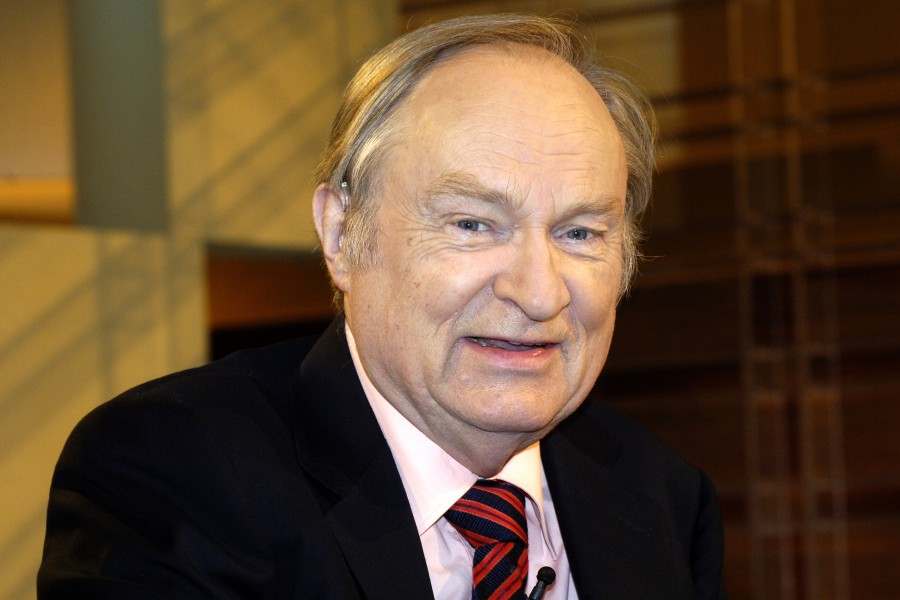

Last month saw the launch of Mind Week, a campaign by the group Time For Change, which aims to combat this misconception. According to Time For Change, in any given year 8-12 per cent of the population experiences clinical depression, and one in four people will suffer a serious period of mental ill-health in their lives. Such figures are not intended to shock, the group insists, but rather to encourage members of the public to keep an eye on their own mental wellbeing, and recognise that “we all have mental health, just as we all have physical health”. Like all media campaigns, Time For Change is scattered with celebrity endorsements, in this case from public figures who have forged successful careers despite battling severe depression, such as Stephen Fry, Melvyn Bragg and Alastair Campbell. It might be well worth asking Minelli if he considers Fry’s most serious bout of suicidal depression, 20 years ago, the point at which society should have written him off, or the point at which his situation was “unalterable”.

Those who appropriate the language associated with terminal illness — for example, citing the onerous duties borne by family and friends — and apply it to the mentally ill, can only cause those who admit to mental illness to become more sidelined by society. I am sure that I am frequently a burden to those around me, mainly when I shirk my turn to do the washing up. More seriously, most of us, in sickness and in health, do constitute obligations to our families, and in turn, are obligated. But the more we think of the elderly and the ill as burdens, of their lives as somehow useless, the more we force on sufferers a sense of duty to take themselves off our hands. Extending the same approach to the mentally ill can only pressure those who already feel lonely and isolated to do the same. In 1941, after years of mental illness, Virginia Woolf wrote a note to her husband explaining that she was committing suicide because “I can’t go on spoiling your life any longer.” If we lose fewer Virginia Woolfs in future, it will be Time For Change, and not Ludwig Minelli, that we have to thank.

Tags: Standpoint