The Angry Brigade, Theatre Royal, Plymouth

reviewed for The Times, 26 September 2014

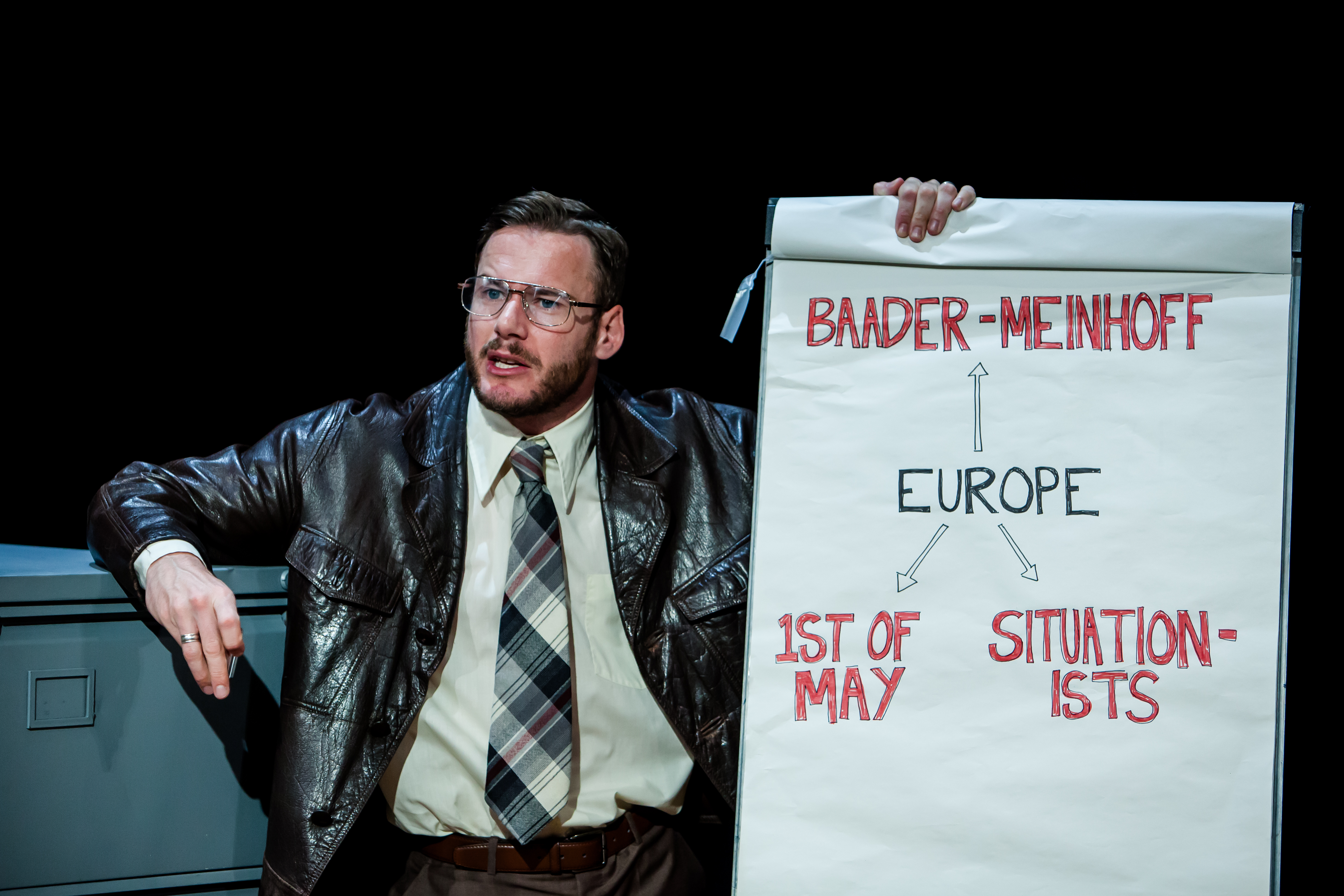

Felix Scott leads a police team in The Angry Brigade

![]()

Remember when a group of privately educated anarchists bombed the home of the Secretary of State for Employment? Perhaps you don’t, but if you’re one of the thousands who saw This House on stage or on livescreen, you will know that the playwright James Graham has a knack for diving into our collective political memory and retrieving the absurd and the inexplicably forgotten.

In The Angry Brigade, Graham returns to the 1970s, shifting his focus to the political counterculture and to a low-level bombing campaign by Britain’s first urban guerrillas. This is a play of mirror images. In the first half we watch four young police officers hunt down the self-styled Angry Brigade, a previously unknown group who have just claimed responsibility for a series of attacks on Establishment figures. Led by Felix Scott’s introspective philosopher-cop, our heroes in the force are trying to understand a new enemy in their own angry generation.

So it’s no surprise that in the second half, the cast swap roles: we meet not four cops, but four overly verbal anarchists, the intellectual crack troops of the Angry Brigade. We’re immersed into their world, and thanks in part to a vulnerable, eloquent performance from Patsy Ferran it’s here that the production really enthrals.

As we’re frequently reminded, a tad too portentously, the Angry Brigade were Britain’s first “homegrown terrorists . . . the enemy within”, but there is something pedestrian and pathetic about this protest movement: hamstrung by self-doubt, shy of shedding blood yet big on propaganda. Germany had the Baader-Meinhof gang, France the Situationists, but Britain had a few university drop-outs living in a commune in Stoke Newington. Graham has put his finger on something essential here. In times of global recession and unrest, why is there so rarely blood on the streets of Britain?

No emerging playwright can beat Graham at explaining political ideas on stage (the police presentation on anarchy is a treat). If there’s a caveat it’s that the victims of terror are grossly unsympathetic — especially those played by a straining, affected Harry Melling. However, while Graham is an articulate conduit for radical frustration, he’s clear-eyed about the Brigade’s selfish naivety. He’s great on subtleties of class and Melling comes into his own as Ferran’s insecure state-educated lover. Graham’s witty play deserves a London run.