The Glass Menagerie, West Yorkshire Playhouse, Leeds

an edited version of this review appeared in The Times, 18 September 2015

The Glass Menagerie is a pressure-cooker of a play. In Depression-era St Louis, Tom and Laura are trapped at home by their domineering, nigh-demented mother Amanda, a faded Southern belle muttering frenetically about the “17 gentle-men callers” who once queued up to court her.

So far, so Tennessee Williams, but in Ellen McDougall’s forensic production for Headlong Theatre, Williams’s first significant play is stripped back to its bleakest vision. We’re in early Pinter now, or even Sarah Kane.

Fragile Laura’s disability is the central mystery of the text: is she a cripple, or broken into hypochondria? In McDougall’s astute deconstruction of The Glass Menagerie, she’s hobbled by a brutal platform heel. Erin Doherty limps around the black box stage with one foot bare, the other clamped like a vice. Pimping out her daughter to potential husbands, Amanda reassures her that “all pretty girls are a trap, a pretty trap, and men expect them to be”. Yet it’s Laura, not Tom, who is caught in femininity’s bear trap.

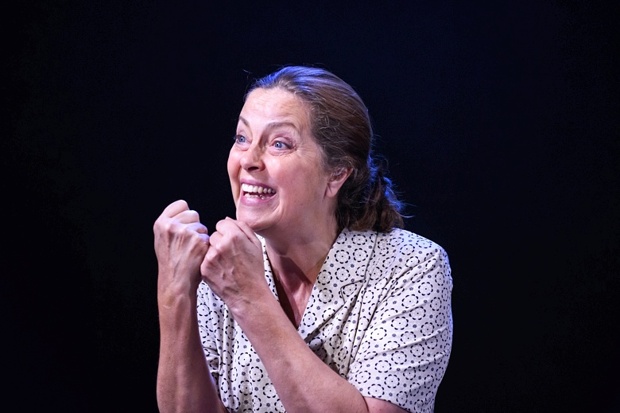

The star-billing is Greta Scacchi as Amanda, shorn of film-star glamour. It’s a tough role, and Scacchi struggles to break beyond Williams’s one-note hysteria. When Tom confronts her, there’s room for a more lucid self-defence, especially given that McDougall’s sharp feminist framework has attuned our sympathy to these women’s limited choices. Instead, Scacchi loses herself in the babble of Amanda’s inanities, even, on press night, stumbling over some of the language of Williams’s rambling monologues.

This leaves space, however, for Tom Mothersdale to establish his star presence as Tom, nervy, desperate to escape. His older self, the play’s narrator, is assured, if regretful, but it’s a fluent transition into the coiled spring-wire of a boy we meet in his mother’s home. Eric Kofi Abrefa too is captivating as Jim, the longed-for suitor. There’s been much talk of ‘colour-blind’ casting recently, and here, it works both ways. To anyone who wants to read it there, the casting of a black suitor can add resonance to this white Southern family’s social desperation, but in McDougall’s anti-naturalistic production, it’s not like we need to take anything at face value.

Above all, this production is McDougall’s triumph. As the elements tear the set apart, there’s clear influence of her work with German directors such as Sebastian Nübling (she successfully brought Roland Schimmelpfennig’s Idomeneus to London’s Gate Theatre last year). Richard Howell’s lighting too does justice to Williams’s preoccupation with natural versus artificial light. It’s all painfully uncomfortable. As it should be.