The Marxist at the Met and her choir of the homeless

written for The Times, 22nd March 2016

Image credit: Jooney Woodward

The last time Penny Woolcock was in a rehearsal room, she was at New York’s Metropolitan Opera, walking the Polish baritone Mariusz Kwiecien through her production of Bizet’s The Pearl Fishers. Woolcock is used to big budgets: her first production for the Met, John Adams’s Oppenheimer-drama Doctor Atomic, simulated on stage the aftershocks of the world’s first nuclear weapons test. Now, she’s sitting in a circle in Manchester’s dusty Methodist Central Hall, teaching the rhythms of Bach’s St Matthew Passion to Mark, who’s spent many of the past ten years homeless.

Streetwise Opera, which works with the homeless and vulnerable, is staging The Passion as a promenade performance in Manchester’s Campfield Market Hall over the Easter weekend: a quartet from the Grammy-nominated choir The Sixteen will sing the trickier numbers conducted by Harry Christophers, and James MacMillan has composed a new “resurrection finale” to a libretto by the cast about their experiences of deprivation.

It’s not such a stretch for Woolcock as it might seem. She’s still a radical at 66, although her once spiky scarlet hair has now flattened to an unremarkable rust sobriety. Known initially as a documentary maker, she has always been defined by the urge to confront her viewers with the voices of the people that we prefer to ignore.

Her 2010 film On the Streets documented the culture and makeshift community of homelessness on its own terms. (“I can’t wait to be next raped,” says one woman. “If I get raped again, it keeps them lot happy. Maybe I might feel something.”)

Woolcock is in thrall to the shadow of the social pariah: her more recent Going to the Dogs was an even-handed observation of the world of dog fighting and the (usually) men who own dangerous dogs. She likes to compare the fatality rate in that illegal, working-class sport to the statistics in upper-crust shooting and horse racing, an approach that caused a flood of angry debate when the film was shown on Channel 4 in 2014.

Is her new career in opera, for an old-school Marxist, a compromise of principle? Not really. “Sure, at the Met the ticket prices mean you get a certain type of audience, but you also get the resources to create something really special. That matters to me hugely, the shot at artistic excellence.”

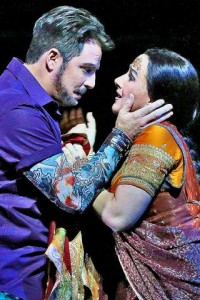

Matthew Polenzani and Diana Damrau in Woolcock’s production of The Pearl Fishers

The CV of excellence matters to her new cast, too. When I visit rehearsals, Anita, experiencing opera for her first time, proudly recites Woolcock’s back catalogue; Matt, a recovering gambling addict, plays Judas with a quiet self-loathing to rival any professional performance, then tells me he’s learning to focus “just like they do at the Met”.

If well-mannered Penny Woolcock is learning to work the establishment, her work in opera is still guaranteed to cause disquiet. She made the transition into the genre with an astonishing, haunting film of The Death of Klinghoffer, Adams’s version of the hijacking of the cruise ship Achille Lauro in which a Jewish-American tourist, Leon Klinghoffer, was killed by Palestinian terrorists.

It’s one of the most beautiful films I’ve seen; it is also powered by an empathy for the underprivileged killers that it often denies to their spoilt, bourgeois Jewish-American victims. Alice Goodman, the librettist, recently complained that collaborating with Adams on Klinghoffer destroyed her career, but it doesn’t seem to have done Woolcock much harm. She tells me that in September, her production of The Pearl Fishers will have its second revival at ENO, confronting any opera-goers who might expect the prettiness of Bizet’s orientalist fantasy with the poverty of a modern Bangladeshi setting.

On boycotts and protests — the Met’s latest production of Klinghoffer, directed by Tom Morris, was heckled in performance — Woolcock is sanguine. “It’s really important that people see things before they make up their mind.” It’s not the approach she has always sustained herself. Arrested at 17 for Trotskyite agitation in Buenos Aires, where her parents were British expats, she has been in and out of hard-left movements for most of her life. “Then, of course, it was all about sustaining the purity of the ideology. I was boycotting other Marxists, left right and centre.”

Like most of her fellow travellers, she’s critical of Israel, but nowadays has no time for a cultural boycott: “I don’t think I’d work on a piece that was directly funded by the Israeli government, but why should I spend my time condemning other people’s ways of building bridges?”

Has she settled down to late-middle-aged liberalism? Not entirely. She’s still waiting for the revolution, still happy to defend Julian Assange — even George Galloway. Naturally, she’s a Corbynista. “The Labour party has lost two elections in a row, so I don’t know who in the parliamentary Labour party can turn around and complain Jeremy Corbyn is unelectable . . . With these hideously obscene levels of inequality, tinkering around the edges of it is just never going to work.”

Yet The Passion’s scope is small: only about forty vulnerable participants can take part, most already “success stories” elsewhere (Mark now lives in his own flat; Anita was referred by an organisation called Moodswings).

On my way from the rehearsal to the railway station, I walk past nine people begging on the streets. Isn’t this, too, just “tinkering around the edges”? “In the Seventies, I was a Trotskyite and there was all this idea that unless you had a revolution, nothing else was worth doing. Now I think that’s nonsense. Small acts of kindness, of love, keep us all going. And I really, profoundly believe in the power of art to effect social change.”

What does that mean? “What’s really powerful about being an artist, we can go into places that other people can’t go. We can do things that other people can’t do and we can hear conversations without having to report them to the police.”

In 2012, that meant shadowing young men from the warring Burger Bar Boys and Johnson Crew street gangs in Birmingham. The police took Woolcock to court to try to force her to hand over raw footage of gangsters allegedly incriminating themselves in crimes, even as she tried to broker peace in the city. Her court victory was life-saving, literally.

“Throughout the whole process, there were people saying that no one should talk to me, that I was working with the police. And then, if talking to me had meant they ended up giving evidence to the police — that would have been the end for them. The end.”

For Woolcock, it was a new beginning. For the resulting film, One Mile Away, she enlisted the help of James Purnell, a former culture secretary, as producer and got advice from Jonathan Powell, Tony Blair’s chief of staff at the time of the Good Friday Agreement. “In my revolutionary days, we were all against joining forces with anyone who had a single disagreement on anything. So of course, I’ve learnt — with James, we worked really well together; every now and then we’d have a big argument about the Iraq war and then we got on with what we had to do. I think that’s the biggest change, really — and that’s something you do learn putting on huge collaborative projects like an opera somewhere as crazy at the Met. The art of building alliances.”

And for a short while, in Birmingham, that alliance did create change. It hasn’t lasted, though. “The underlying causes are still there and the younger ones are starting the killings again,” Woolcock says. “It’s heartbreaking.”

So what’s the point of a film that gives a small sub-sample of gangsters a project for eight months of filming, or gives 40 homeless people something to do for three months? “That’s still a huge thing for those few people who experience it,” Woolcock insists. “That’s still worth it for each of those individuals. And it’s not just about them. It’s about the audience. If you come to that rehearsal, then walk past those beggars on the streets on your way home, I hope you’re going to smile and say hello to each of them as you pass, because at least we’ve taught you what they could be. I can’t save all of them; I’ve never saved everyone who takes part in my films. But I have humanised them. I hope.”