The Tempest, Cheek by Jowl at the Barbican Centre

reviewed for The Spectator, 11 April 2011

Rarely has a production of The Tempest been as bleak, powerful and urgent as this. The drama is often billed as Shakespeare’s last play, a retiree’s lyrical contemplation of the need for redemption and reconciliation in the later ages of man. The more we learn about Shakespeare’s later career as a collaborator with John Fletcher, the less this artful chronology stands up to scrutiny. But even though productions of The Tempest have become successively dark, in line with wider theatrical trends in the past 60 years, few so completely destroyed any hopeful vision of a better world to come as Cheek by Jowl’s brilliant Russian language production, playing at the Barbican Centre until 16th April.

This heartbreaking, breathtaking bleakness is one of the most obviously Russian elements of the production. This is a drama of raw Slavic emotion – one almost expects a suicide on stage, followed by an anguished cry of yearning for Moscow, or in this case, Milan. Where the translation necessitates a loss of Shakespeare’s rich language, which might to some render an entire production worthless, the language barrier requires non-Russian speaking audiences to respond on a more primal, visceral level. The effect is transcendent.

Igor Yasulovich’s Prospero is tormented, weak, impotently violent and impulsive, his haggard face howling against the elements like a kulak who has lived through 70 years of dispossession and repeated displacement through shifting Soviet regimes. This is Prospero as King Lear against a scotched earth, grief-struck at the loss of his daughter to a dangerous, arrogant young Ferdinand (Yan Ilves). The moment when Prospero turns upon his son-in-law with crazed blows, then falls upon him weeping, begging him for filial acceptance, is heart-stopping.

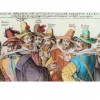

Where the emotional landscape is stark, the staging is abuzz with activity, always engaging, with never a gesture or syllable wasted. This is a tightly controlled and yet exuberant production – right down to the water. Where Jonathan Kent’s production back in 2000 drenched the Almeida until it nearly floated, Donnellan’s uses nearly as much water in narrow, choreographed trickles, wryly directed by spirits onto exact targets: the round heads of unfortunate Italians.

Where Caliban (Alexander Feklistov) comes into his own is in his relationship with Anya Khalilulina’s magnificent Miranda. Like portrayals of Perdita in The Tempest’s sister play, The Winter’s Tale, historical portrayals of Miranda oscillate between highlighting her nature as a royal princess and her nurture on a remote island. For once, here is a Miranda who might truly have been reared on a desert island – utterly feral, she barely rises from her hands and knees, crouching, bounding and playfully rutting with the enthralled Ferdinand. And yet she is utterly feminine, beautiful and delicate.

Where Caliban (Alexander Feklistov) comes into his own is in his relationship with Anya Khalilulina’s magnificent Miranda. Like portrayals of Perdita in The Tempest’s sister play, The Winter’s Tale, historical portrayals of Miranda oscillate between highlighting her nature as a royal princess and her nurture on a remote island. For once, here is a Miranda who might truly have been reared on a desert island – utterly feral, she barely rises from her hands and knees, crouching, bounding and playfully rutting with the enthralled Ferdinand. And yet she is utterly feminine, beautiful and delicate.

This is chilling – it is a short leap from her innocence of the nudity taboo, which delights Caliban, until we are forced to watch as she leaps, utterly unaware of the consequences, into the arms of the opportunist rapist, Ferdinand. Yet in her boundless energy, she delights us, inciting the same fascination as she does in the dangerous men around her. It is profoundly, brilliantly unsettling.

There are moments when the constant commentary on Russian politics seems to diminish Shakespeare’s plot. The replacement of a vengeful harpy with an ephemeral Kremlin show trial for Prospero’s betrayers drains the scene of the chaotic, natural energy the island spirits represent. But these are small complaints to make about a production so phenomenal, so full of inspiration, and so adept at conveying Shakespeare’s essential drama through shifting cultures.

This is what Global Shakespeare should be. If you can’t get a ticket for this week, go to Russia just to see it revived in May or June. You won’t regret the trip.