There’s nothing patriotic about William Blake’s Jerusalem

written for The Spectator, 14 January 2016

In this week’s diary, Tristram Hunt puts his money behind Jerusalem as a new English National Anthem. ‘God Save the Queen’ isn’t going anywhere as the United Kingdom’s theme, but there’s room for a local melody when Team England take to the field (as the MP Toby Perkins pointed out, it’s hard to square English rugby fans singing ‘God Save The Queen’ as we face off against the Welsh). But Tristram, for the love of the Holy Lamb of God, please don’t let it beJerusalem.

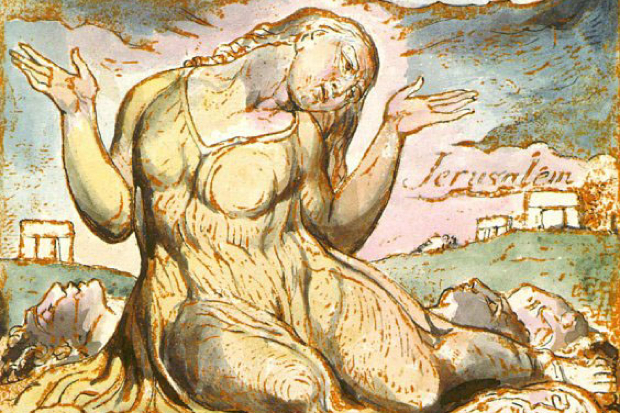

The truth about Jerusalem is that it isn’t a patriotic poem at all. Parry’s music gives the hymn an upbeat tempo – especially with the booming orchestration by Edward Elgar – but William Blake’s original words are as laced with resentful irony as Shostakovich’s Leningrad symphony. Famously, Blake asks four questions in succession, and the answer to each is a resounding no. Christ’s feet never trod in England; the Lamb of God didn’t gambol – preposterous as the image is – around the Cotswolds; the Holy Spirit wasn’t regularly spotted in London fog; and most directly of all, there was no sense of Jerusalem in the dark Satanic mills of the Industrial Age. The consequent fantasy of building a New Jerusalem in England is widely understood by anyone who studies Blake to be a stonking parody of Napoleonic Era nationalism. Even in 1804, no one sung and danced about their own ‘mental fight’ and expected to be taken seriously.

Instead, Jerusalem encapsulates Blake’s fears about the all-too-easy suppression of the individual spirit. The ‘Satanic mills’ may refer to the Albion Flour Mills, large-scale mills near Blake’s home which were burned down anonymously after they threatened to put smaller millers out of business. (So, Jerusalem as an anthem would celebrate anti-capitalist arson. Which makes us virtually French.) But when Blake wrote about ‘mills’ elsewhere he usually used them as a metaphor for institutionalised religion – which, like Marx after him, he considered the natural ally of capitalism and monarchy. (He was wrong, of course, but that’s another fight for another day).

Consider Blake’s apocalyptic vision, Vala. On nine successive nights, Blake dreams that the universe unravels: on the ninth, superstition (Mystery) is lifted from the earth. ‘Art thou she that made the nations drunk with the cup of Religion?’ declares the spirit Tharmas. ‘Go down, ye Kings and Counsellors and Giant Warriors…Go down with horse and Chariots and Trumpets of hoarse war… Let the slave, grinding at the mill, run out into the field. Let him look up into the heavens and laugh in the bright air.’ Religion, War, Kings and Mills = bad; bright air and sunshine = good. After all, Blake, who was charged with sedition in 1803, was the non-conformist son of English Dissenters. He had little time, too, for the Glastonbury myths of St Joseph of Arimathea which permeate the verse. Instead, Blake satirised, rather than shared, the quasi-religious nationalism of his contemporaries. There’d be a heavy irony in the Queen’s modern subjects appropriating his words to swear loyalty to a collective cause.

I’m less convinced than Blake that there’s anything wrong with the gentler forms of nationalism, per se. When the Telegraph’s Tim Stanley debated this with me on Sky News yesterday, Tim argued that English nationalism is a destructive force, that rise of differing national symbolisms heralds a Balkanistic breakup of the Union. That’s overly pessimistic: a certain pride in Englishness should reassure us that the Celts aren’t the only Britons with an interesting history. It subverts the narrative which presents England as a soggy bland mass, against which ‘subaltern’ cultures proudly define themselves. It’s harder to hate your Sassanach oppressors when they’ve got an upbeat soundtrack.

But please, not Blake. He’d turn in his grave to know that English rugby fans already wave St George’s flag along to his words. Other prominent options are tricky, too. Swing Low, Sweet Chariot, is already sung by rugby fans, but is abstract and overly religious. So isI Vow To Thee, My Country – which even harps on unpatriotically about England not being as pure as Heaven. Land of Hope and Gloryis closely associated with the genocidal Cecil Rhodes, and singing about the need to push our national boundaries ‘wider and wider’ seems a little distasteful nowadays. But there’s always Ivor Novello’sRose of England, which celebrates the rose’s truly English ability to blossom in rainy showers. Like the best patriotic songs, it brings back memories of British bravery during the Blitz of World War II, and it doesn’t have any dodgy references to Empire, either.

England football fans may feel they’re used to God Save the Queen. But as the historian Oskar Cox Jensen points out, the anthem is not even three hundred years old, which only counts as traditional if you’re American. It’s not very fair on republicans, either. You can’t reasonably implore God to confound the politics of the monarch’s enemies while you’re up to your own knavish tricks to cut the Civil List – or if you’re Prince Charles. For monarchist, republican and rebellious heir alike, Rule Britannia is much more fun. And like God Save the Queen, it actually emerged as a dissenters’ song, asserting a vision of liberty despite the worst efforts of George II. (‘Thee haughty tyrants ne’er shall tame / All their attempts to bend thee down / Will but arouse thy generous flame.’) Even the exhortation to ‘Rule the Waves’ is less aggressive than it is defensive – if you’re an island nation, you ruddy well should rule your own coastguard. The trigger-word, ‘empire’, is never once uttered.

‘Britannia’, of course, prohibits it from serving as a solely English anthem. And the role of UK National Anthem isn’t up for grabs. But like it or loathe it, God Save The Queen isn’t enshrined in any law. Like the best of British traditions, it’s an unwritten custom. So likewise, an English anthem won’t need Toby Perkins MP, or anyone else, to enforce it. All it needs is a few lusty sports fans to pick a song, and start bellowing. They could even make like the Irish rugby team, and commission a new one. Just please don’t make it Jerusalem.