Two Ados

For Tate’s acerbic Beatrice, there’s rarely a clue that Benedict might actually have some sway over her heart. One would love to help her escape from the type-casting of Vicky Pollard, but before her complaint that ‘against my will, I am sent to bid you come in to dinner’, one can almost see her mouth forming the words, ‘am I bovvered?’ By contrast, Best at the Globe is visibly weakened when she overhears the emotional suffering she is supposedly causing Benedict although, to the discredit of the production, you’ll have to sit centrally to see exactly what’s going on in these scenes.

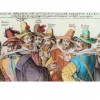

Eve Best at Shakespeare’s Globe

Best is partnered by a superb Charles Edwards, and their relationship is fierce and bitter. When he offers to help after his best friend has jilted her cousin, her simple response is heart-stopping and deadly serious: ‘Kill Claudio’. Tate and Tennant, on the other hand, seem to treat the near-tragedy as an opportunity for a drunken dare – but their lighter touch renders the comic ‘gulling’ scenes an absolute pleasure.

The low comedy of the incompetent night watchmen is, for once, delivered with freshness and clarity in the Tennant-Tate production, thanks to John Ramm as Dogberry, a role that his equivalent at the Globe, Paul Hunter, buries in incomprehensible buffoonery with guffaws and physical ticks. What’s funny about Dogberry is his inability to understand his own long words; 16th century malapropisms are usually hard enough for a modern audience to understand, without extra absurdities on top.

But Hunter’s colleague, Philip Cumbus, manages to imbue the often doltish role of Claudio with real depth. For Cumbus, Benedict’s best friend has all the insecurities of the young soldier. He’s better with fists than words, and there’s a touching innocence to his constant fear of being shown up by the sophisticates around him. Cumbus’s is a nuanced, deeply promising performance.

Back at Wyndhams, Rourke slims down the play by cutting much of the dialogue that explores the fear of inconstancy and superficiality in love – the intellectual backbone to Hero and Claudio’s story. Instead, she adds a new, ingenious symbolic network – Charles and Diana masks pop up on the disco floor, and Hero walks up the aisle in a direct copy of Diana’s adolescent fantasy of a wedding dress.

The trope works beautifully with the ‘80s setting and the theme of a fairytale gone badly wrong, but a more aggressive, textual insertion throws the whole relationship out of kilter again. Crucial to the play is the economic relationship between fathers and daughters, in a world in which Hero is, repeatedly, ‘a jewel’ for Claudio to buy from her father, and who can be replaced, in the marriage bargain, by her father’s niece if need be.

Rourke inserts a mother figure for Hero, who takes lines and plot devices usually given to Beatrice’s father, Antonio. Relationships between fathers and daughters have changed between 1599 and 1983, but this seemingly small change in dynamic cuts the play off from its Renaissance roots, as well as jarring the meter of several keys lines of poetry. By the time Leonato turns, ‘my brother had a daughter’ into ‘my wife has a niece’, his relationship with Beatrice has become more distant, and his language less reassuring.

Nonetheless, the change is a reminder of Rourke’s inventiveness in a delightful, clever, production. It’s a joy to see a director acknowledge the relationship between this play and Romeo and Juliet – in a surprise, Lurhmann-esque scene that adds a new take on Claudio – even if it slightly reduces the impact of the play’s denouement. But if you want a fuller look at Shakespeare’s text, head down to the Globe.

Pages: 1 2