Wolf Hall / Bring Up The Bodies, Aldwych Theatre

Wolf Hall and Bring Up The Bodies, Aldwych Theatre, reviewed for The Spectator, 25 May 2014.

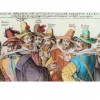

Ben Miles as Thomas Cromwell and Lydia Leonard as Anne Boleyn in Wolf Hall. (Photo credit: Alastair Muir)

In Hilary Mantel’s Tudor England, it never stops raining. As she writes in her evocative programme note for the RSC stage adaptation of Wolf Hall, she first envisaged the life of Henry VIII’s political fixer, Thomas Cromwell, as ‘a room: the smell of wood smoke, ink, wet dogs and wet wool, and the steady patter of rain’. I’d heard, correctly, that Jeremy Herrin’s production was every bit as close and claustrophobic as Mantel’s novel. So as I set off, it seemed a disadvantageous prospect to spend a day of blazing summer sunshine cooped up with six hours of theatre, reviewing the double bill of Wolf Hall, and its sequel, Bring Up The Bodies.

In fact, thanks to Herrin’s startling, vivid production, time flies, especially in the second play, a Faustian thriller in which Anne Boleyn’s fate tightens inexorably around her neck. Mantel’s double-Booker winning novels reimagined Henry VIII’s break with Rome through the life story of the lawyer who made it possible: Thomas Cromwell, blacksmith’s son and meticulous strategist, the first great success of an emerging Tudor meritocracy – or, if you prefer, a brutish Steerpike minus the polish, clambering to power on the headless bodies of inbred aristos.

Cromwell, played here by a charismatic Ben Miles, disposes of two inconvenient wives for Henry VIII, Katherine of Aragon by long-protracted annulment, then Anne Boleyn, on the executioner’s block. But for Mantel, he’s a working class hero. A voracious reader when not spiking heads, he’s probably Michael Gove’s hero too.

Mike Poulton’s supple adaptation underscores Mantel’s focus on class struggle: the religious war between tradition and reformation becomes one between old families and the new men, with their English Bibles and pesky modern notions like universal literacy. But Poulton and director Herrin also capture Mantel’s sense of historical truth as something always just eluding us, memory as always failing at the crucial moment.

We may never know whether Anne Boleyn really committed adultery, the play suggests. As a historian, I’d beg to differ: Cromwell’s case against her was riddled with inconsistencies, often requiring her to have been in two parts of the country at once. But I’m seduced by Mantel’s vision of a world where the truth hardly matters. Voltaire called historians merely ‘gossips who tease the dead’, and they have left us a ghostly kaleidoscope of different Anne Boleyns: icy Machiavel, nervous hysteric, proto-feminist, Mean Girl, theological scholar, incestuous whore.

In Herrin’s enthralling production, each Anne has her turn centre-stage. As Cromwell collects each piece of gossip about her, we see Anne’s flirtations played out. But does even he believe in the scenes he’s staging for us? It’s all smoke and mirrors, but a good piece of political theatre is enough to damn a queen.

Much of the visual texture of the novels is lost in Poulton’s adaptation for the stage. And I’d have liked to have seen more of Cromwell’s domestic life (the play has been cut since its Stratford run). The sudden deaths of his wife and daughters in an epidemic are passed over in almost an instant, haunting though the moment is. I missed watching Cromwell create a mafia family of adopted sons: Josh Silver, one to watch, is an excellent Rafe Sadler, but Richard Rich and Thomas Wriothesley, who would emerge from Cromwell’s tutelage the Tudor court’s most notorious turncoats, are both excised in the transition from the novel.

This barely matters, thanks to Ben Miles’ compelling performance as Cromwell. But the web of gossip and intrigue that surrounds Cromwell in the books – has he taken a mistress? Has he killed her husband for her?– is thinned out as Anne becomes the enigma, Cromwell the straight man.

Mantel’s starting point was a pair of Holbein portraits: Cromwell’s is distinctly unflattering (‘I look like a murderer!’ ‘Did you not know?’ asks his son, in the novel), while the portrait of his rival Thomas More radiates decency. Yet it is More, not the thickset Cromwell, who keeps ‘heretics’ in cages in his private garden, for personal torture sessions. Looks aren’t everything. Herrin’s production is more superficial: Miles’s Cromwell is kitted out as a matinee idol, his usual shaggy grey hair died jet black, barely aging through a decade’s drama, while John Ramm’s More, with his straggly wig and heavy breathing, looks every inch the paedophile schoolmaster of caricature. Outclassing this More is all a bit too easy.

But Miles’ Cromwell meets his equal in Lydia Leonard’s captivating Anne Boleyn. By turns witty, shrewish, calculating, neurotic, Leonard gives life to every rumour you’ve ever heard about Anne, but grounds her in a core of vivacious determination. Infinitely watchable, it’s she who makes the hours fly by in a career-making performance. Nathanial Parker is also surprisingly convincing against type as an affable Henry VIII, though Leah Brotherhead is distractingly affected as Jane Seymour, and Henry’s sickly eldest daughter Mary. But quibbles aside, this is a major theatrical event. Don’t settle for one play – see both.