Women of Troy, Women of Syria

written for Index on Censorship, March 2015.

see also “From Euripides to “The Archers”, The Times, January 2015

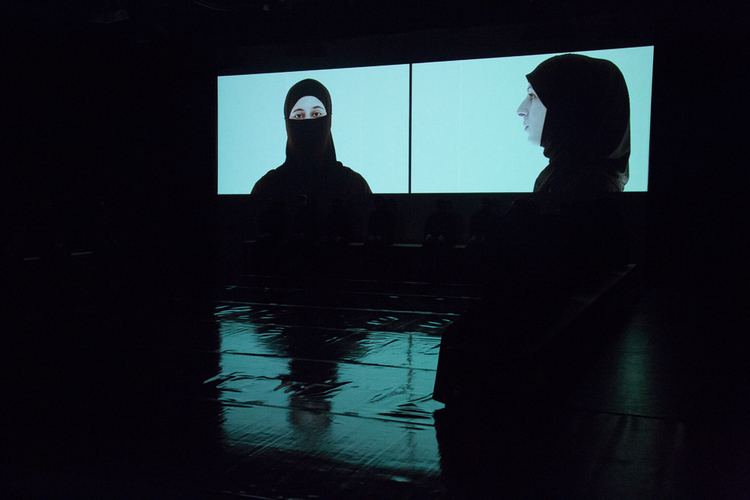

Syrian Trojan Women in performance. (Photo credit: Lynn Alleva Lilley)

In a shabby Amman apartment, 23-year-old Raneem has been practicing her stage make-up again. One of the 600,000 Syrian refugees living in Jordan, her clothes now come from bargain racks and charity bins, but she’s still never knowingly underdressed.

For Raneem, getting her husband’s permission was the hardest thing about joining the Syrian Trojan Women project. “He was worried about men seeing me, about me talking with men. But I kept going to the rehearsals because it was women I wanted to share stories with. There are things women experience in war – what it is to be a mother in war – that only they understand. I think he was jealous: he didn’t come to the performance, not because he disapproved, but because he was jealous of what I had found.”

Women’s space or not, when Trojan Women was first performed in 415BC, it shocked, precisely because it told the truth – to men. Euripides’ play was performed to an Athenian audience, shortly after the Athenian army had enslaved the entire female population of the island of Melos. “Euripides puts women’s voices on stage – whoever is silently watching, those who have suffered get to confront them,” says Reem, a performer and translator with the project. “Men die in wars, but women get left behind, and have to feed children and endure the chaos.” Fatima, an older woman from the siege city of Homs, tells me “in school, I had heard of the Fall of Troy: but only of the men fighting, Achilles and Hector”. The only woman she knew featured was Helen, the whore. “I couldn’t identify with her,” says Fatima. “But in Euripides’ play, there are so many other women. I am Hecuba: in her own house, her palace, she knew who she was. When her house was destroyed, her identity, her dignity, was gone too.”

Nobody wants to be Helen in the play. Sex, especially sex in war, isn’t talked about. But whispers of rape haunt the rehearsal room: no one talks of personal experience, but everyone admits to knowing a friend’s sister or cousin who has been assaulted by President Assad’s enforcers. In the play when the Trojan princess Cassandra is taken into slavery, she laments her humiliation as Achilles’ concubine. “When we recite Cassandra’s lines,” says one woman, “it’s like a storm has lifted from the room.”

It’s not just sex and death, however, that makes Euripides’ characters live on, two thousand years later. Trojan Women is full of greyer, moral choices. Sham, a young woman from Damascus, has a sneaking sympathy for Talthybius, the conflicted Greek herald who guards the female prisoners in Trojan Women. He reminds me of my uncle,” she says. “ He still works for Assad’s security forces, even though he hates it, because he can’t desert. But he nonetheless helped us escape.” In Trojan Women, Talthybius comforts his prisoners – in modern productions he usually sneaks them cigarettes – but that doesn’t mean he intervenes when the last heir to the Trojan throne, a toddler, is throne to his death from the rocky city walls. For survivors of the Syrian conflict, this is all too human a choice.